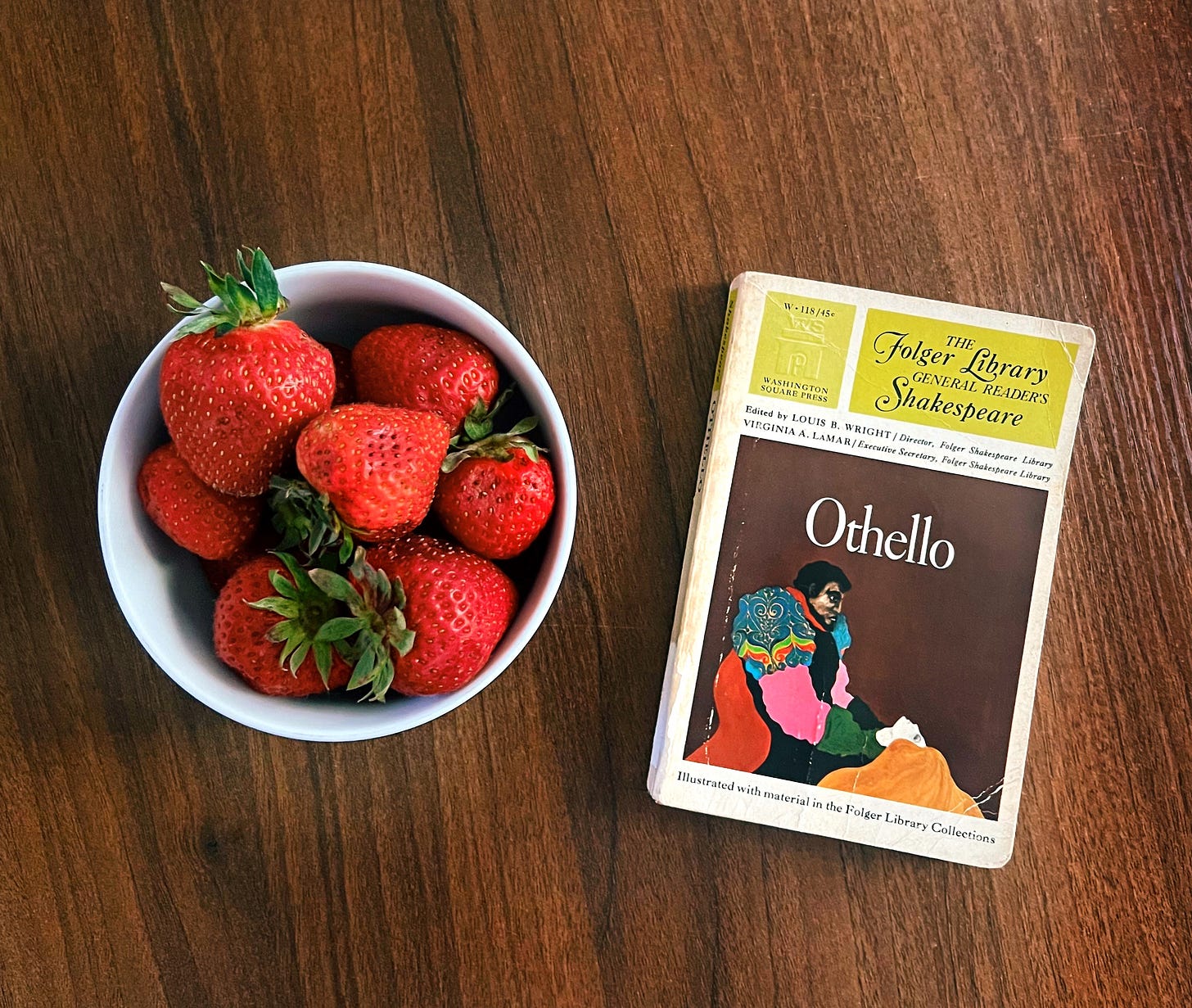

Strawberries and Othello 🍓

On Desdemona's handkerchief and the implications of red fruit.

I am a collector by nature. As a kid, it was Kitchen Littles and Polly Pockets (we liked tiny things in the ‘90s, okay?) Lately, I’ve been into Folger Library and Signet Classic editions of Shakespeare. I love finding a marked-up copy so I can read and respond to the previous owner’s notes, creating a conversation spanning decades (thanks, Gertrude Whipple, 1979). Recently, I was skimming through Othello searching for marginalia when my eye caught a line about a particular item…

A brief rundown: The play follows the Moorish general of the Venetian army, Othello, his wife, Desdemona, and his trusted ensign, Iago, who lies and manipulates Othello into believing his wife is unfaithful. Othello descends into a murderous rage, not realizing the truth of Desdemona’s innocence and Iago’s deceit until it’s too late because he is a gullible dum-dum.

The most crucial plot point, the one the entire play hinges on, is Desdemona’s handkerchief. Othello gives it to his wife as a token of his affection for her, but it soon represents his growing jealousy and mistrust when Iago uses it to plant a seed of doubt and imply her infidelity.

It’s also covered in strawberries.

“She may be honest yet. Tell me but this:

Have you not sometimes seen a handkerchief Spotted with strawberries in your wife’s hand?”

Historically, strawberries were symbolic of love, romance, and purity. Some traditions say they represent the Virgin Mary. The Middle Ages associated them with temptation and sin. All these qualities, when applied to a woman, hold her to an impossible standard where she is both virgin and whore. This is Desdemona’s burden. From Hamlet to King Lear, Shakespeare’s works were greatly influenced by the Medieval period, so it seems a small assumption that he would be aware of these connotations. By this reasoning the design appears purposeful. The strawberry recalls Othello’s love and devotion, the sin of Desdemona’s alleged adultery, her oh-so-precious purity, and the lady herself as an object of temptation.

Red alludes to the play’s bloody end, but touching back on purity, the “spotted” strawberries on the handkerchief could also be interpreted as blood stains left on the marital bed, embroidered as they are on a (virginal) white cloth reminiscent of a blanket. Desdemona brings it up after Othello accuses her of cheating, telling Emilia to “lay on my bed my wedding sheets…and call thy husband hither.” It’s either a not-so-subtle attempt to remind him of her loyalty or a hint at another theory that their marriage is not yet consummated. Having sex with Othello would prove she is a virgin, and his accusations are baseless. If the marriage is not consummated, it adds a layer of complexity to Othello’s behavior and gives further insight into his insecurities.

“The worms were hallowed that did breed the silk,

And it was dyed in mummy, which the skillful

Conserved of maidens’ hearts.”

I assumed the strawberries on the handkerchief were embroidered in red, but Othello says the silk was “dyed in mummy,” which refers to the ancient practice of extracting a substance called bitumen from mummified bodies, the color of which was typically brown/black. I won’t beat the symbolism into the ground here, but you know. Apt. Race is such an underlying component of the play that I wondered if it would still factor in when I started mining the strawberry stuff, and here it is. But then there’s the whole “maidens’ hearts” thing, and we’re back to virgin blood.

When Othello describes the lore of the handkerchief to Desdemona, that it is a family heirloom passed down through generations, that it has “magic in the web of it,” that it contains the power to strengthen or weaken love, depending on how carefully or carelessly it’s handled, he is feeding into superstition, and using the handkerchief as a warning to Desdemona: “To lose’t or give’t away were such perdition as nothing else could match.” His attachment to the handkerchief illustrates an excessive reliance on an object imbued with too much sentimental value.

Because Othello derives so much meaning from a stupid piece of fabric, Desdemona unwittingly takes on an added layer of purity, and he conflates her with the virtue of the cloth, so much so that his fragile ego can’t take the thought of her defiling herself, and he resorts to murder. His willingness to believe Iago’s version of events is frustrating because Desdemona is a ride-or-die (literally!) kind of gal. We could get into how easily Iago manipulates people, first rallying allies against Othello using racial stereotypes, then Othello against Desdemona using sexist stereotypes, and how these people are susceptible to such things based on how society has primed them to believe the worst in Black men and women—but we’d be here all day.

“They are all but stomachs, and we all but food;

they eat us hungerly, and when they are full,

they belch us.”

Here, Emilia reflects on the nature of relationships between men and women. Her remark suggests that men are primarily driven by their physical appetites and view women as objects of desire to fulfill their needs, discarding them when they’re done. It exposes (through appropriate food-based sentiment) the pervasive misogyny riddled throughout the play.

In the end, Othello murders Desdemona in their bed—the ultimate symbol of bloodshed on the marriage bed—and the meaning of the strawberry shifts to jealousy, violence, and their tragic consequences.

While researching the history of the strawberry (or Fragaria x ananassa if you’re fancy), I was led down a very fascinating, very gross, mummy-fluid information hole, which I feel compelled to share with you. Mummia refers to using mummies in medicinal preparations, including “a black resinous exudate scraped out from embalmed Egyptian mummies.” People took it as medicine or even as an aphrodisiac. By the 17th century, ground-up mummy flesh was used as a popular paint color called mummy brown. They stopped producing the color in the 1960s because the only company still making it ran out of mummies. Think about that the next time you look at paintings in a museum.

I’ve wanted to write this newsletter since I first launched my blog, Eating Books, with a recipe for crackling bread from To Kill a Mocking Bird. It barely scratched the surface of how food in that novel touches on race, class, and Southern hospitality. I didn’t think people would want to read a broader dissection of those elements or scroll through walls of text (“Just get to the recipe already!”—you, probably), so I buried the idea. But I know what you’re thinking: food doesn’t always have to mean something, does it? Well…indulge me.

I would also like to emphasize that I am neither an academic nor a journalist. I am just a curious person who has built my entire online persona around this particular niche and would like to explore it more deeply. This is just one interpretation of fiction through a gastric lens, and though some of it might be reaching, especially in the future when I try to convince you that Derek Smalls’ cucumber dick is genuinely significant to the plot of This Is Spinal Tap, I hope it’s still worth reading about.

Become a Paid Subscriber!

I plan to keep fictional food posts free for everyone, but if you want to support my writing, consider becoming a paid subscriber. For $5/month or $30/year you’ll get:

Public posts (fictional food), subscriber-only posts (everything else), full archive

Literary Mixtapes (a musical companion to the fictional food newsletter), curated and thematic playlists to enhance your reading experience

More to come…

You can also support the newsletter by recommending it on Substack, sharing it with your friends, or following me on Instagram or Twitter.

Currently

Eating…

My beloved grandmother just passed after a long battle with dementia, so I am writing from a plane heading toward Ohio. By the time you read this, I imagine I’ll have gone to the funeral, hugged my family, and eaten my weight in our poor imitations of her best recipes: meatloaf, egg noodles, and mashed potatoes (technically my grandfather’s specialty). Future Rebecca: Can confirm. Rest easy, grams.

Reading…

I work in publishing, so I’m reading one of our upcoming books to prepare for a marketing brainstorm. I just finished Yellowface by R.F. Kuang for Stay Home Book Club, the pandemic-era book club I created, and I started reading The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov for #ReadingDavidBowie, my attempt to read all of David Bowie’s 100 favorite books.

Writing…

More newsletters! You can anticipate the aforementioned This Is Spinal Tap analysis, food as racial metaphor in Toni Morrison's novels, gluttony in Dante’s Inferno (also: cannibalism!), and the extent to which divine food affects The Iliad, among other things. Other than that, I am hard at work on a novel, which I’ll share more about if I ever gain the confidence.

Hi!

Loved this!

I agree with Ruth! Time to crack open a copy of Othello.

Sadly the closest I got to it was the movie “O” which somehow loosely based it around Othello but based in high school and focused around basketball.

Cant wait for the next!

I enjoyed this, Rebecca! I’ll now have to reread Othello with Desdemona’s strawberry handkerchief in mind. I’ve often thought of looking into food motifs in literature, though more in the hunt for recipes than meaning. I admire your approach to the subject and look forward to future posts. Condolences on the loss of your grandmother.